Mast cell tumours (MCTs) are the most common canine cutaneous neoplasia and can vary widely in biological behaviour. All breeds can be affected, but dogs of Bulldog descent (eg Boxer, Pug) and certain breeds, including Golden Retrievers, Labradors and Shar-peis, are at increased risk (White et al., 2011).

Pathophysiology

Mast cells contain cytoplasmic granules consisting of a variety of bioactive substances, including heparin and histamine. The release of these mediators on the degranulation of mast cells can contribute to some of the systemic clinical signs observed in dogs with MCTs, including vomiting, diarrhoea, pyrexia, peripheral oedema and, rarely, collapse.

The c-Kit gene, a proto-oncogene encoding the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT, is implicated in the pathogenesis of canine MCTs and activating mutations in this gene have been linked to tumour development and aggressiveness (Bellamy and Berlato, 2022).

Clinical signs

Most dogs with MCTs are clinically well aside from solitary or occasionally multiple cutaneous masses, most commonly located on the trunk and perineal area. Mast cell tumours can vary widely in appearance and may be mistaken for non-neoplastic lesions. Low-grade MCTs are typically slow-growing over many months (Figure 1), whereas high-grade MCTs can grow rapidly to a large size and are often ulcerated (Figure 2). Dogs with visceral metastasis can present systemically unwell with neoplastic cavity effusions.

Clinical signs secondary to mast cell degranulation may be observed, such as fluctuations in tumour size, peritumoral oedema/erythema or systemic signs including gastrointestinal upset or, rarely, collapse.

Prognostic factors

Before further diagnostics and treatment, it is important to understand the prognostic factors associated with canine MCTs as these factors will influence case management. There are many prognostic factors, and they should all be considered when assessing a case as no single factor is entirely predictive of biological behaviour and outcome.

Histology

Histological grade is the single most reliable prognostic factor when assessing canine cutaneous MCTs. Cutaneous MCTs are routinely graded according to the Patnaik system (grade 1, 2 or 3) or the Kiupel system, in which tumours are categorised as low- or high-grade depending on their histological features (Kiupel et al., 2011; Patnaik et al., 1984).

Histological grade is the single most reliable prognostic factor when assessing canine cutaneous mast cell tumours

The histological grade of cutaneous MCTs is prognostic. Dogs with Patnaik grade 3 tumours have significantly shorter survival compared to Patnaik grade 1 and 2 tumours. Similarly, dogs with Kiupel high-grade tumours have poorer outcomes compared to low-grade tumours.

Both grading schemes are used concurrently, with the Kiupel grade helping predict the biological behaviour of Patnaik intermediate-grade (grade 2) MCTs, which can behave unpredictably. For Patnaik intermediate-grade tumours, markers of proliferation such as mitotic index (MI), Ki67 index and AgNOR index can help determine if biologically aggressive behaviour is to be expected (Bellamy and Berlato, 2022; Webster et al., 2007). For example, MCTs with a Ki67 index above 1.8 percent are associated with a poorer prognosis (Maglennon et al., 2008).

Clinical stage

Clinical stage is also predictive for survival and often graded using the World Health Organization clinical staging system for MCTs presented in Table 1 (Owen et al., 1980). Metastatic rate increases with tumour grade and is often to local lymph nodes (LNs), liver, spleen and, rarely, bone marrow and the lungs. Increasing stage of the disease is correlated with a worse prognosis, with a median survival time of just 110 days in dogs with stage IV disease (Pizzoni et al., 2018).

| Stage | Substage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | One tumour incompletely excised from the dermis, without regional lymph node involvement | a | Without systemic signs |

| I | One tumour confined to the dermis, without regional lymph node involvement | b | With systemic signs |

| II | One tumour confined to the dermis, with regional lymph node involvement | ||

| III | Multiple dermal tumours; large, infiltrating tumours with or without regional lymph node involvement | ||

| IV | Any tumour with distant metastasis, including blood or bone marrow involvement | ||

Other factors

Other prognostic factors include c-Kit mutation status, KIT expression pattern, tumour location and signalment, although this is not an exhaustive list. Although some breeds of dogs, including Pugs, Boxers and dogs of Bulldog descent, are predisposed to MCT development, they generally seem to develop lower-grade tumours (Smiech et al., 2017).

Activating mutations in the c-Kit gene are common in canine MCTs, especially high-grade tumours, with one study demonstrating mutations in 26.2 percent of MCTs (Letard et al., 2008). C-Kit mutations are significantly associated with decreased disease-free interval, increased risk of tumour recurrence and decreased overall survival time (Vozdova et al., 2019; Webster et al., 2007).

Activating mutations in the c-Kit gene are common in canine mast cell tumours, especially high-grade tumours, with one study demonstrating mutations in 26.2 percent

The KIT expression pattern is also associated with prognosis. Normally, KIT is expressed in the cell membrane of mast cells (KIT staining pattern 1). But in some neoplastic mast cells, KIT is expressed focally (staining pattern 2) or diffusely (staining pattern 3) throughout the cytoplasm. Increased cytoplasmic KIT expression is associated with an increased risk of local recurrence and reduced overall survival (Kiupel et al., 2004).

Tumour location is also prognostic: those located in subungual or perineal/inguinal regions (especially if located on the prepuce or scrotum) are associated with more aggressive behaviour.

Further investigations

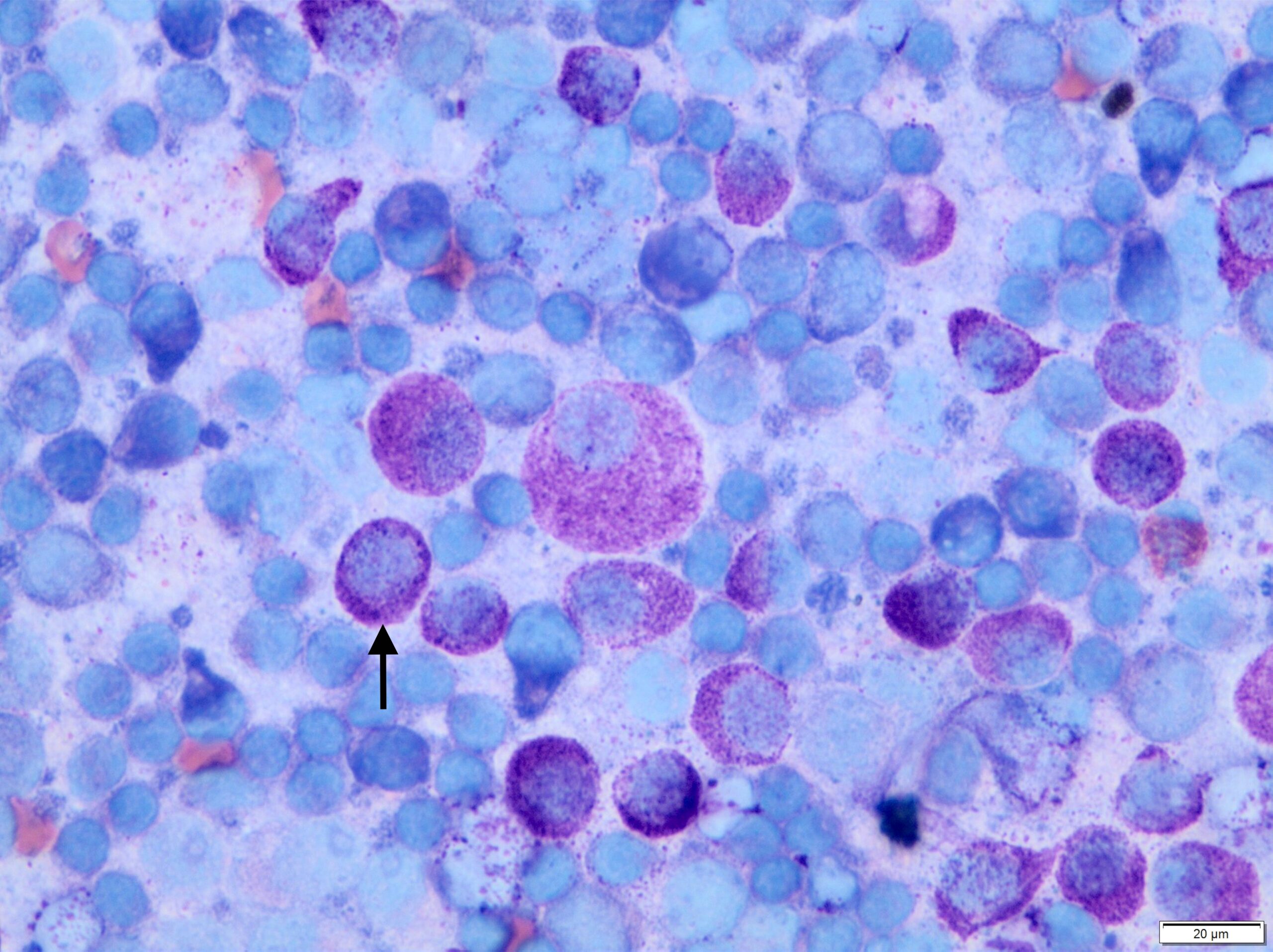

In most cases, MCTs are diagnosed easily via fine needle aspirate cytology. The round cells contain characteristic metachromatic cytoplasmic granules (Figure 3), although high-grade MCTs may lack granules and can, therefore, be challenging to differentiate from other round cell tumours.

Full preoperative staging includes haematology, biochemistry, urinalysis, regional LN aspirates and ultrasound-guided liver and spleen aspirates, regardless of ultrasonographic appearance (as the liver and spleen can appear normal despite harbouring metastatic disease).

If the MCT is amenable to wide surgical excision and lacks any of the above negative prognostic factors, surgical excision could be performed initially with staging undertaken if histology identifies a high-grade or “high-risk” MCT.

Preoperative cytological grading or incisional biopsy for histology could be considered to guide decision making, although both methods can underestimate MCT grade in a small proportion of cases (Scarpa et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2018). Thoracic imaging is rarely indicated as pulmonary metastasis is very uncommon; however, it may be prudent before invasive or expensive treatment to rule out comorbidities. To reduce the risk of MCT degranulation, chlorphenamine should be administered before aspiration of the primary tumour, LNs, liver or spleen.

Investigating metastasis

Assessment for LN metastasis should not be based solely on LN size or location. A sentinel lymph node (SLN) is defined as the first LN within a lymphatic basin that drains the primary tumour. Historically, the SLN was often considered the closest LN to the tumour, but this is not always the case as lymphatic drainage patterns can be unpredictable; one study demonstrated that 42 percent of dogs with MCTs had an SLN different to the anatomically closest LN (Worley, 2014). If there is any doubt over the location of regional LNs, SLN mapping procedures, such as indirect CT lymphography or contrast-enhanced ultrasound, may be performed.

Regarding LN size, around 50 percent of normal-sized regional LNs harboured metastatic MCTs in one study (Ferrari et al., 2018). Therefore, aspirates of LNs should always be obtained regardless of their size.

Finally, LN cytology is only 75 percent sensitive for detection of MCT metastasis, so draining LN extirpation for histopathology should ideally be performed in all cases to avoid undiagnosed residual metastatic disease (Fournier et al., 2018).

Treatment

Surgical excision

The initial treatment of choice for MCTs is surgical excision, where possible. Historically, 3cm lateral margins were recommended for all MCTs, and although this is still ideal for high-grade MCTs, 1cm and 2cm lateral margins are acceptable for low- and intermediate-grade MCTs, respectively. Excision should always include removal of one uninvolved fascial plane, irrespective of histological grade. Sentinel/regional lymph nodes should also be excised if identified as metastatic during initial staging.

Removal of metastatic lymph nodes significantly improves survival in dogs with stage II mast cell tumours, and many dogs with low- or intermediate-grade stage II MCTs can enjoy a good prognosis

Removal of metastatic LNs significantly improves survival in dogs with stage II MCTs, and many dogs with low- or intermediate-grade stage II MCTs can enjoy a good prognosis and be treated with surgery alone without the need for adjuvant chemotherapy (Marconato et al., 2018). As discussed above, LNs should ideally be removed, even if cytologically negative for metastasis, due to the risk of false-negative results.

Post-excision adjuvant therapy

If complete surgical excision is achieved for a low- or intermediate-grade MCT, it is possible no further treatment is required. But if excision is incomplete, several options are available including revision surgery, adjuvant radiation therapy (RT), electrochemotherapy (ECT) or systemic chemotherapy/targeted therapy (although local treatment options are preferable if no metastasis is present). Active surveillance is also an option as only 10 to 30 percent of incompletely excised low- or intermediate-grade MCTs recur.

Adjuvant systemic therapy (chemotherapy or targeted therapies (tyrosine kinase inhibitors)) is recommended in most dogs with high-grade MCTs due to the high metastatic risk, even where complete surgical excision is achieved. If the mass is incompletely excised, further local treatment is also advised; if these options are not possible, the systemic therapies employed to reduce the risk of metastatic disease will also target residual local disease. Systemic therapy should also be considered in cases with negative prognostic factors other than just tumour grade, such as high-risk tumour locations or high proliferation indices.

What if excision is not feasible?

If an MCT cannot be excised, local treatment options in the gross disease setting, including RT, ECT or systemic chemotherapy/targeted therapy, should be considered. Additionally, tigilanol tiglate (Stelfonta) is a recently approved novel treatment for non-resectable canine MCTs. It has a reported complete response rate of up to 88 percent, with 89 percent of dogs recurrence-free 12 months after treatment (De Ridder et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2021).

In any dog where gross disease remains, it is important to reduce the risk and consequences of MCT degranulation. The author uses a combination of H1 receptor antagonist chlorphenamine and proton-pump inhibitor omeprazole for as long as significant gross disease is present.

There are a variety of chemotherapy options for canine MCT, mainly revolving around vinblastine, lomustine, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) or combinations thereof. A 12-week vinblastine protocol (administered weekly for four doses, then every other week for four doses) is a well-tolerated adjuvant protocol for low- to intermediate-grade MCTs where chemotherapy is indicated (eg high-risk tumour location). A combined vinblastine/lomustine protocol can be considered for high-grade MCTs.

There are a variety of chemotherapy options for canine mast cell tumours, mainly revolving around vinblastine, lomustine, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) or combinations thereof

In situations where the primary tumour cannot be excised or treated with RT, ECT or tigilanol tiglate, TKIs such as toceranib or masitinib can be considered. These have a reported overall response rate between 43 and 82 percent; prednisolone is used alongside these protocols and if required can also be used alone in a palliative setting, with a reported overall response rate of 20 percent (London and Thamm, 2019).

This list of chemotherapy protocols is by no means exhaustive. As treatment recommendations depend highly on histological prognostic factors, disease stage and independent patient factors, consultation with a veterinary oncologist is sensible before starting chemotherapy.