Endotracheal tube (ETT) placement is an essential part of safe anaesthesia in cats and dogs as it allows for the administration of anaesthetic agents with oxygen and the removal of carbon dioxide from the patient’s airway.

Advantages of intubation include protecting the airway from regurgitant matter, reducing workplace pollution by inhalational anaesthetic agents and facilitating intermittent positive pressure ventilation. Potential complications include tracheal mucosal damage or tears, which may result in subcutaneous emphysema or pneumothorax. Excessively long ETTs may result in hypoventilation or bronchial intubation. Complications are, fortunately, uncommon and generally avoidable by selecting an appropriate ETT with careful tube insertion and management.

Types of endotracheal tubes

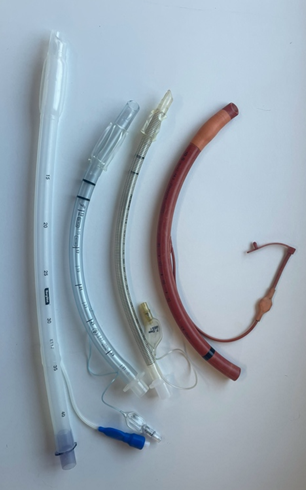

Traditional red rubber tubes have largely been replaced by tubes made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or silicone, which are softer materials that are less likely to damage the trachea (Figure 1). ETTs may also be reinforced, making them more resistant to kinking. This, in turn, makes them useful for head and neck surgeries, where the tube is at risk of extreme bending and obstruction. Reinforced and silicone tubes are often softer and more flexible, which can make placement more challenging; using a stylet helps placement by making the tube more rigid.

Reinforced and silicone tubes are often softer and more flexible, which can make placement more challenging; using a stylet helps placement by making the tube more rigid

Parts of endotracheal tubes

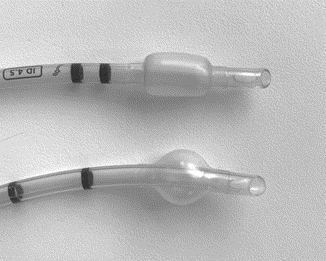

ETT cuffs are inflated when the practitioner connects a syringe to a pilot valve, thus creating a seal within the trachea. Cuffs may be low volume/high pressure (LV/HP) or high volume/low pressure (HV/LP) (Figure 2):

- LV/HP cuffs form a more effective seal but contact a smaller surface area of tracheal mucosa, potentially increasing the risk of tracheal damage due to pressure

- HV/LP cuffs contact a larger tracheal area with lower pressures but can form wrinkles when inflated, increasing the risk of leakage around the cuff

Uncuffed tubes have the disadvantage of not providing an airway seal. Still, they may be easier to place in some circumstances (eg where pathology results in a narrow airway or for very small patients).

Murphy’s eye is a hole near the distal end of the tube that allows flow in case the ETT tip becomes obstructed. Details printed on the tube include the internal diameter (mm), length markers and a radio-opaque line.

How do I select the right endotracheal tube for my patient?

When selecting the right endotracheal tube for a situation, consideration needs to be given not only to the material and cuff but also to tube length and diameter.

Correct tube length can be estimated as the distance from the incisors to the thoracic inlet. With the exception of reinforced tubes, most ETTs can be cut easily, but the connector must be firmly replaced into the tube to avoid disconnection during anaesthesia. Cutting the tube at an angle helps with refitting the connector. Overly long tubes may result in increased apparatus dead space, which can increase the work of breathing and lead to hypoventilation. Inadvertent bronchial intubation with a long tube can lead to atelectasis in the contralateral lung. Placing a short tube may result in the cuff not being positioned within the trachea.

When selecting the right endotracheal tube for a situation, consideration needs to be given not only to the material and cuff but also to tube length and diameter

Wider tubes have less resistance to flow, which is beneficial to reduce the work of breathing and lower the risk of airway obstruction (eg due to mucus). However, an inappropriately wide ETT can damage tissues of the upper respiratory tract, or, in very rare cases, get stuck. A narrow tube may not produce an airway seal with a safe level of cuff inflation. The ideal tube is the widest size that is easy to place with no resistance during intubation.

HV/LP cuffs and those not fully deflated may be more difficult to place through the larynx, particularly in cats. Brachycephalic breeds of dogs have relatively narrow tracheas compared to their body size, so tubes with a narrower diameter are often required.

What is the correct cuff inflation?

Correct cuff inflation is essential. Overinflation results in high pressure, which can impede blood flow in the tracheal mucosa, leading to tracheal necrosis or even tracheal tears; insufficient inflation results in an incomplete seal.

Cuff pressure can be measured using a manometer or a digital cuff inflator syringe (AG Cuffill; Figure 3) to inflate and measure the cuff pressure, which should be 20 to 30cmH2O (Hung et al., 2020). A different type of cuff inflation syringe (Tru-Cuff) contains a colour-coded pressure indicator.

Another approach is the minimum occlusive volume (MOV) technique for cuff inflation, which involves two people. One person manually inflates the chest by squeezing the reservoir bag with a closed APL valve to a peak airway pressure of 20cmH2O while the other listens for an air leak around the ETT (Hung et al., 2020). The cuff is gradually inflated until the leak disappears. Digital palpation of the pilot valve after cuff inflation should be avoided as this technique is inaccurate to assess correct inflation (White et al., 2017).

Digital palpation of the pilot valve after cuff inflation should be avoided as this technique is inaccurate to assess correct inflation

In one study, the MOV technique was used in 50 dogs undergoing anaesthesia and cuff pressure was subsequently measured; only 14 percent were correctly inflated whereas 76 percent were overinflated (Hung et al., 2020). The same study compared the MOV technique to Tru-Cuff and AG Cuffill. AG Cuffill had significantly more correctly inflated cuffs (86.7 percent) compared to 50 percent with Tru-Cuff and 3.3 percent with MOV.

Using endotracheal tubes in cats – risks, pitfalls and more

Cats have small airways and are at greater risk of laryngospasm, necessitating topical laryngeal administration of lidocaine prior to intubation.

Airway complications associated with anaesthesia are almost twice as common in cats (9.4 percent) compared to dogs (4.9 percent) (McMillan and Darcy, 2016). Laryngeal trauma may occur during tube placement; using a laryngoscope and an appropriate tube design and size will reduce the risk. Tracheal damage or tears may result from cuff overinflation (Hardie et al., 1999; Mitchell et al., 2000) or traction on the tube, which may occur when patient recumbency is changed without disconnecting the breathing system. Eleven cases of tracheal rupture in cats were reported to the Veterinary Defence Society over a 10-year period; all were undergoing dental procedures and involved red rubber tubes with LV/HP cuffs (Adshead, 2011).

Endotracheal tubes suitable for use in cats are made of flexible material with thin-walled, low-profile cuffs, making laryngeal visualisation and tube placement easier while minimising the risk of tracheal trauma

In feline patients, uncuffed tubes may be easier to place and can remove the risk of tracheal damage due to cuff overinflation. However, this option does not offer a complete airway seal. Red rubber tubes should be avoided due to the risk of tracheal injury, particularly in this species. ETTs suitable for use in cats are made of flexible material with thin-walled, low-profile cuffs, making laryngeal visualisation and tube placement easier while minimising the risk of tracheal trauma (eg Shiley Hi-Contour, Covidien).

Confirmation of correct placement

While a laryngoscope allows the practitioner to visualise the ETT entering the larynx during placement, observation of chest movements synchronous to changes in the breathing system bag suggests the tube is located in the trachea. However, the gold-standard method for confirming correct placement at induction of anaesthesia is the production of carbon dioxide in expired gases monitored with capnography.

| Key points – Cuffed endotracheal tubes are suitable for most cats and dogs – Material, cuff type, length and diameter of tube are all important considerations – Cats are at particular risk of tracheal damage or tears – Aim for a cuff pressure of 20 to 30cmH2O for airway protection while avoiding tracheal damage – A cuff manometer or digital cuff syringe is required to accurately measure cuff pressure |